“I’m allowing myself, at last, to wait a long time with my sorrow. To wait with it as long as it takes” – Memorial Days.[1]I have loved the work of Geraldine Brooks for a very long time – particularly her novel The People of the Book (2008, Penguin Books). I found this book in favourite bookstore not long after Dad … Continue reading

Geraldine Brooks

Author

A rogue force

Glioblastoma.[2]For the etymology of this word, I relied upon my favourite source, Merriam-Webster online. You can find the entry here: “Glioblastoma.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, … Continue reading I had not heard of this word until it arrived, without warning and without invitation into our family’s vocabulary in late November 2024. So many English words have a messy, mixed-up and mysterious ancestry but not this one; my sisters and I decided to call it the “nasty little fucker” anyway. Glioblastoma: glio-blast-oma. GLIO. “Glio” derives from the Ancient Greek word “glia” (γλία), meaning “glue.” BLAST. The Greek origin of “blast” as a word root is “blastos” (βλαστός), meaning “sprout,” “germ,” or “bud.” This root is used in scientific and biological contexts, particularly in the combining form blasto-, to refer to embryonic cells or formative stages of development, such as in words like “blastocyst” or “blastogenesis.” While the English word “blast” can refer to an explosion or sudden sound, its etymological roots in combining form are Greek, specifically tied to growth and embryonic development as in “shoot, bud, embryo, germ.” OMA. There is no hiding the origins of this word; from Ancient Greek (-ωμα) it simply means “tumour.” The nasty little fucker took root and bloomed with ruthless force, booming and tearing through our family’s world—and most devastatingly of all, through Dad’s.

A glioblastoma is like a rogue force inside the brain—a former helper cell that turns against its own system. It doesn’t just grow; it infiltrates, manipulates, and spreads. It’s unpredictable, aggressive, and deeply personal in its destruction. I have begun to think of it as the Heathcliff of the brain’s biology. Like Heathcliff in Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, glioblastoma begins as part of the structure—familiar, even trusted. But something shifts. It becomes consumed by its own drive, refusing to follow the rules of healthy function. It lashes out, not with emotion, but with relentless replication and invasion. Just as Heathcliff disrupts the lives of everyone around him—twisting relationships, haunting generations—glioblastoma disrupts the brain’s networks. It doesn’t stay in one place. It spreads into nearby tissue, corrupting what was once stable and functional. And like Heathcliff, it’s hard to remove. Even when confronted directly, it leaves behind traces, scars, and consequences. Make no mistake, this nasty little fucker is ruthless and there is no remedy.

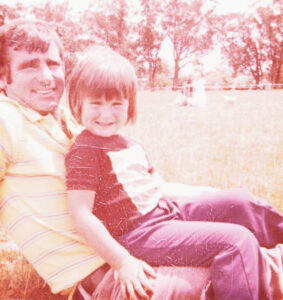

Dad didn’t know that we called it the nasty little fucker, and despite his propensity to use the “f” word, I don’t think he would have liked it—mostly because he refused to accept his terminal diagnosis, and this was both a blessing and a curse. It meant that he could wake up each day and turn his face to the sun, knowing it would be there waiting warmly to greet him. Amongst the many cruelties, one of the merciless things about Dad’s tumour was its location in an area of his brain responsible for regulating body temperature; he had always hated the cold and now he was perpetually so, even when it wasn’t. He became a heat seeker, finding the warmest places to sit inside and outside the house, steadfast in the belief that the clouds would soon pass. His capacity to remain positive was awesome, in the fullest sense of the word. The week before he passed, Dad bravely asked the palliative care doctor if it was worth getting a second opinion on second surgery to remove the tumour, now growing aggressively second by second. That nasty little fucker had taken so much already, but Dad refused to let it have the last word. He reached for something beyond its cruelty—he reached for more, he reached for hope.

Surgery, chemotherapy and radiation were offered to Dad. He placed his trust in the surgical body engineer with the soft voice, the oncologist who wore humour like armor, and even the radiation doctor who delivered the blunt truth: “Make no mistake—this cancer is going to get you.” Dad heard and put his hand up for it all. He chose to defy the certainty of death by trusting in the possibility of care. He had major brain surgery at the Royal Melbourne Private Hospital on 24 November 2024, where most of the tumour was removed with minimal impact on his brain function and quality of life. Dad seemed to return to normal and was given the prognosis of 18 months to 2 years. Despite not wanting to say out loud “Ballarat Regional Integrated Cancer Centre,” he walked steadfastly through the hospital doors and started radiation and chemotherapy on 20 December 2024. On 25 December 2024 Dad had a major subdural hematoma or brain bleed and was rushed back down to the Royal Melbourne Private Hospital to emergency. The decision was made that it was too soon to operate again, and that radiation and chemotherapy treatment would be paused while the brain bleed settled. On 27 January 2025 Dad had another small brain bleed, and he was once more rushed down to the Royal Melbourne. He underwent burr-hole surgery to drain the entire bleed and relieve the pressure on his brain. There would be no more radiation or chemotherapy treatment, and the prognosis shifted again, this time to six months, maybe 12. Dad stopped going to see the oncologist in the Canadian tuxedo and was referred to a palliative care doctor. By the end of April 2025, Dad wasn’t well enough to leave the house and began having home visits; the prognosis shifted again to two to four weeks. He was admitted to Gandarra Palliative Care Unit on Thursday 8 May, thinking that his stay there was only temporary, and once his condition was stabilised he would be coming home. On Friday night we kissed him goodbye with thoughts of coffee to be had in the autumn sun tomorrow; he reportedly had a nice chat with one of the palliative care nurses later in the evening about the joys to be found in driving heavy vehicles and went to sleep. Dad did not wake again and passed away on Monday 12 May 2025 at 3:30am.

Sourdough, sisters and love

When Dad was diagnosed, I began writing in a smaller sized journal—both to fit it inside a Virginia Woolf cloth case from my sister Sally with “Books are the mirrors of the soul” on the cover, and to set these entries apart from my others. I set aside my black pen and wrote in blue ink. I came to think of these as “Dad’s cancer diaries,” in remembrance of Audre Lorde’s Cancer Journals, and documented everything I could. The writing in these diaries is hard and reading the writing harder still, but there is one theme running which softens the return—the relationship that sits there between my sisters and me. I can’t remember when the three of us spent so much time together, certainly not since becoming adult women. Sally and I moved away from home to go to university when Natalie was not yet a teenager. Ursula K. Le Guin wrote in The Lathe of Heaven,[3]Le Guin, U. K. (1971). The Lathe of Heaven, Scribner, p. 158. “Love doesn’t just sit there, like a stone; it has to be made, like bread; remade all the time, made new” and if there is any light to be found in the dark of Dad’s brain cancer it is in the sourdough of sisterly love we found ourselves baking. Sally was the flour, planning and coordinating and keeping things grounded. Natalie was the salt, the supporter and the subtle flavour that uplifted us when we most needed it. I was the water that flowed and connected, bridging feelings, ideas and people. During the short five months of Dad’s illness, our attempts at making sourdough sometimes failed and the bread refused to rise—sometimes too heavy on the flour, sometimes too much salt, sometimes not enough water—but we continued to remake ourselves over and over again. That sourdough-sisterly love dipped in olive oil and dusted with dukkha, is a flavour I will remember long after the last slice disappeared. Thought Dad dismissed sourdough as “too crusty for comfort”, somehow the memory of the time with my sisters still rises soft and golden.

One evening, over a wee dram of fine Scotch whiskey, Sally and Natalie turned to me with gentle insistence, asking if I would share some words on our behalf at Dad’s funeral. My heart skipped a beat; I loved that they trusted my way with stories and speeches, but the very thought terrified me. My heart started to race because even though I’ve spent years writing, finding the right words for this moment pressed heavily on my chest—not least of all because my number one proofreader was no longer here to read or hear them. One of the greatest pleasures for me as Dad’s daughter was the opportunity to share my writing, especially writing about our family, with him. Although Dad never considered himself a writer or a reader, he always took the time to review anything I sent his way and in true Keith Raymond fashion, he would make corrections where he saw fit, mostly to ensure that dates and facts were all in the right place. Those kinds of details were important to Dad but so too was family and the love that resides so deeply there. “Thanks, Beth,” he once said after reading a poem I had written about Mum, “you bring tears of joy to my eyes.” In August this year, my new book Odd Shoes and Other Essays will be released, and Dad was the most wonderful writing companion I could have asked for during the final stages. The manuscript was due on 1 December 2024, but my editors kindly chose to ignore the sound of this deadline as it rushed by. They extended instead a caring hand and a new submission date. Each day Dad would shuffle up to the spare room in mismatched shoes laces untied, holding a fresh cappuccino carefully in both hands made especially for me and plop himself down onto the sofa bed beside my desk. He would check in with how my writing was going and looking down at his feet ask, “Beth, when you have moment, could you help me with my shoes?” He often said how awful he felt that his diagnosis had slowed down my submission, but I love that my number one proofreader was part of the final process because now it feels like Dad is everywhere in Odd Shoes.

Just write, anything

Friday 5 February 2021 at 4:01pm

Keith and Lyn <kandl@bisi.com.au>

Hi Beth – I have spent most of today prepping the paperwork/technical crap to allow my car project to be finally accepted for Rego.

I must say that although it is a very tedious job it has made me realise just how much work I have put in to bring the project to fruition.

Having said that I have just read your story and found it to be very uplifting and a welcome interlude.

I am printing the story for Mum to read I’m sure that she will enjoy it too.

You are probably aware that there are a couple of typos but I’m sure that you will address them in due course.

Just thinking about my car project, I am getting the feeling that what you are doing or have done with your various projects are not too dissimilar in process to my car project/s !

Love you

Dad xx

The title of this post is “In the wake of grief and glioblastoma: Just write, anything” and yet this is the first time I have written the word “grief.” The word itself is heavy by name and heavy by nature, and besides, I don’t really need to—grief is everywhere in this piece, splashing cold water all over my hands as it sinks right down to its very depths. Silly me! I forgot to wear my gloves, and with no thanks to the nasty little fucker, it has taken me more than two months to be able to write anything beyond scraps and scribbles. If there is grief to be written about explicitly in this moment, it is to be found in one simple question—who is going to be my number one proofreader now? I find myself sitting at the keyboard—sometimes out of habit, sometimes out of hope—imagining him gently saying “Here you go, Beth” as he sets freshly brewed coffee beside my desk. There is an ache in the absence of Dad’s steady presence, the certainty that my words would meet his thoughtful and heartfelt eyes before reaching the world. Now, there is no hand to correct my dates or fuss over the facts, no voice to offer another anecdote, no signs of assurance that my words meant something—meant something to him. There are no words to write if Dad is not there to read them; and so, I don’t.

On my shelves are several “how to write” guides, many of them by women writers I love and adore. I cast my eyes over the ones I often turn to in times of trouble—Hélène Cixous’ Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing,[4]Cixous, H. (2003). Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing, Columbia University. Ursula K. Le Guin’s Steering the Craft and Dancing at the Edge of the World,[5]Le Guin, U. K. (1989). Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places, Groove Press; (2015). Steering the Craft, First Mariner. Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird,[6]Lamott, A. 1994). Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, Anchor Books. Remembered Rapture[7]hooks, b. (1999). Remembered Rapture: The Writer at Work, Henry Holt and Company. by bell hooks, and Elizabeth Gilbert’s Big Magic[8]Gilbert, E. (2016). Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear, Penguin Publishing Group. but today I find no counsel in their words. My focus slips, dulled by the blue grey bruises inked into my heart the moment Dad left. I am not sure how long I sit there; body, mind and soul blurred. And then I remember the two word mantra from Natalie Goldberg, “Just write” in Writing Down the Bones.[9]Goldberg, N. (2016). Writing Down the Bones: Freeing the Writer Within (30th anniversary ed.), Shambala. “Take out another notebook, pick up another pen,” she urges, “And just write, just write, just write.” In 2021, Natalie released a Writing Down the Bones card deck based on this philosophy in response to one of the questions she receives most frequently: “How do I begin?” There are 60 cards, each based on a topic (not a prompt, she is very insistent about that, wanting instead to encourage writing that starts any place, slants, and springs) and while there are no rules about how to use them, Natalie asks for three things. One: “please let go and let writing do writing;” two: “please try handwriting;” and three: please proceed.” And so, I do. I randomly select a card from the deck and draw number #24. I smile wryly at the topic, “WHAT BROUGHT YOU TO THIS PAGE? WHAT DO YOU WANT TO WRITE?” I begin with one word and write—anything.

References

| ↑1 | I have loved the work of Geraldine Brooks for a very long time – particularly her novel The People of the Book (2008, Penguin Books). I found this book in favourite bookstore not long after Dad passed away and read it in one sitting. It arrived just when I needed it and I have held onto it tightly ever since. Brooks, G. (2025). Memorial Days: A Memoir, Hachette Australia. p. 69 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For the etymology of this word, I relied upon my favourite source, Merriam-Webster online. You can find the entry here: “Glioblastoma.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/glioblastoma. Accessed 31 Jul. 2025. |

| ↑3 | Le Guin, U. K. (1971). The Lathe of Heaven, Scribner, p. 158. |

| ↑4 | Cixous, H. (2003). Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing, Columbia University. |

| ↑5 | Le Guin, U. K. (1989). Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places, Groove Press; (2015). Steering the Craft, First Mariner. |

| ↑6 | Lamott, A. 1994). Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, Anchor Books. |

| ↑7 | hooks, b. (1999). Remembered Rapture: The Writer at Work, Henry Holt and Company. |

| ↑8 | Gilbert, E. (2016). Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear, Penguin Publishing Group. |

| ↑9 | Goldberg, N. (2016). Writing Down the Bones: Freeing the Writer Within (30th anniversary ed.), Shambala. |