I may never be happy, but tonight I am content. Nothing more than an empty house, the warm hazy weariness from a day spent setting strawberry runners in the sun, a glass of cool sweet milk, and a shallow dish of blueberries bathed in cream. When one is so tired at the end of a day one must sleep, and at the next dawn there are more strawberry runners to set, and so one goes on living, near the earth. At times like this I’d call myself a fool to ask for more.

― p. 8)

Over the fence –

Strawberries – grow –

Over the fence –

I could climb – if I tried, I know –

Berries are nice!

But – if I stained my Apron –

God would certainly scold!

Oh, dear, – I guess if He were a Boy –

He’d – climb – if He could!

Emily Dickinson

Poem #251 in Emily Dickinson’s poems: As she preserved them (2016, p. 134).

Down in the berry patch

There are some books whose words slowly but surely press onto the roof of your mouth, trickling their juices down into your body, brain, and soul until you are full to popping with the sweet tang of them, an imprint you find yourself longing for in the most unexpected moments. A taste of blackberries by

Doris Buchanan Smith is one of those books for me. It was published in 1973 and found its way into my hands when I was old enough to begin reading books without pictures. The story begins beyond the back fence in a thicket of blackberries, two best friends on a summertime outdoor ramble. Together they race down dirt roads, rock hop across creeks, snitch apples from a gun carrying neighbour, get caught in thunderstorms and daringly hitchhike to safety, and earn holiday spending money and help an elderly lady by scraping Japanese beetles from the grapevines in her garden. That’s when it happens, when the taste of blackberries becomes so much more than about picking fruit. Looking for something a little more exciting than pest control, Jamie begins poking around in a beehive with a stick and the irate insects swarm angrily to deliver defensive punctures to his skin. Within minutes Jamie is dead. The publishers initially rejected the manuscript stating that the subject matter was not appropriate for young readers; I read it from cover to cover. There are ambulances and casket viewings and tears that run like faucets and funerals and thoughts about angels and what happens to bees after they bite.

My younger sister Natalie

flying high.

My Auntie Florence and Uncle Bob owned a berry farm at Badger Creek in the Yarra Ranges, just east of Melbourne. For two weeks before Christmas each year, my sister Sally and I would head down to help pick the fruit for market. Blackberries and boysenberries pulled 30 cents a punnet, while the more elusive raspberries 35 cents. In the dim light of dawn, raspberries were devilishly difficult to find hidden amongst the leafy bushes and more than a gentle tug was sure to crush the ripe fruit, but any damaged goods soon became a delicacy in my Auntie Florence’s kitchen. Blackberry pie, raspberry coulis on vanilla ice-cream, boysenberry jam on fresh scones, warm mixed berry muffins; there was no end to her culinary creations. I never needed to wear any lip gloss during the festive season, they were already tinted a delicious deep burgundy by the time Christmas arrived. Back then in the 1970s, no-one I knew grew blueberries and they weren’t available in the supermarkets either—blueberries first appeared in Australia in 1976 when founding Knoxfield growers Karel Kroon and Ridley Bell reportedly took a tray of 12 punnets from the trial bushes to the Footscray markets in Melbourne. What a strange delightful little fruit they all said! On the other side of the world the humble berry was gazed at in wonder but this time under the microscope by American researchers Jim Joseph and Ronald Pryor. They had discovered that blueberries contained the highest concentration of antioxidants of any known fruit or vegetable at the time. What a super little fruit they said! I feel my ageing body glow with healthy radiance as I pass by the shelf stacked high with fresh blueberries in my local supermarket and join one in two Australians who on average buy 136gram of this low-calorie-vitamin rich superfood.

“I was in America at a very expensive liberal arts college…and I was eating blueberries and I was naked but for my black silk robe” (2021, p. 42).

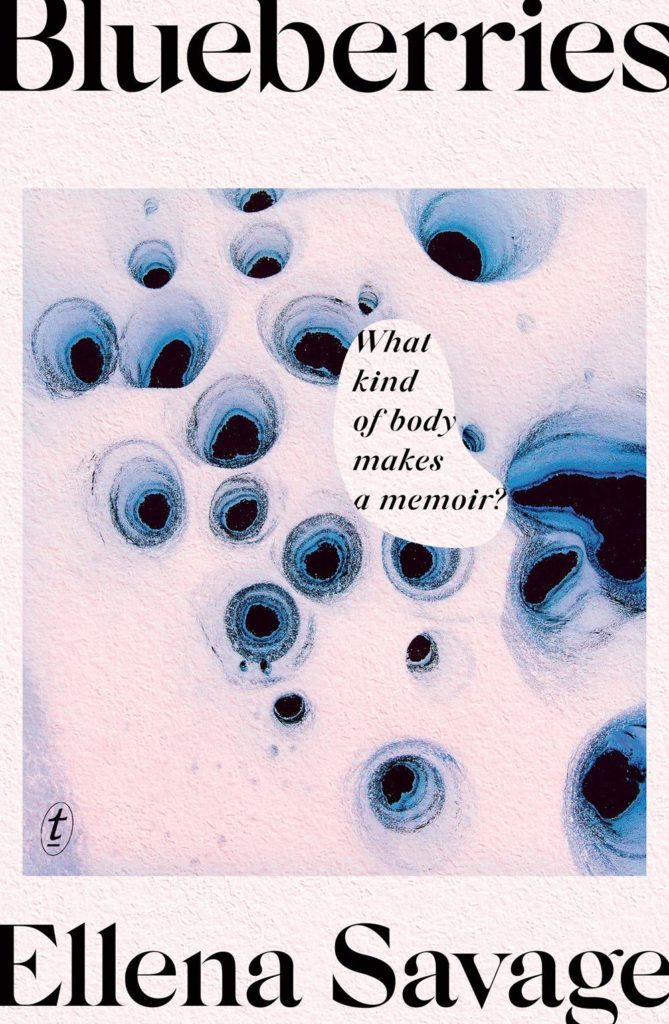

It was my love of berries that drew me to Ellena Savage’s 2021 book of essays sweetly titled Blueberries: What kind of body makes a memoir? The font type is curvy and luscious, the cover image a cross-section expose of this tiny berry’s body in all its diversity. Savage is a young Australian writer whose writing in this text might be loosely and variously described as creative-critical-confessional-experimental-non-fiction-autotheory-memoir. No two essays in this collection are the same and aim explicitly to mess with taken for granted stylistic conventions and genres. Savage takes the reader around the world and across time with long sentences and short meditations on her young-white-race-class-able-bodied privilege to complete, compete, consume, and contemplate self and other crimes committed in the name of. When I started reading Blueberries, I felt a sense of being with her—the essays “Yellow city” and “The museum of rape” re/turn around the drip-drip everyday trauma and brutality of sexual assault when a woman’s body meets the world. “I’ll do anything, just please don’t hurt me” (p. 16), Savage cries while hostage in a Lisbon hotel room when her “body understood for a second that corpses are dismembered to cover up crimes” (p. 6). With her individual memories on collective display she asks, “There are museums for every tragedy, every genocide. Why not the persistent all-encompassing mundane treachery of rape?” (p. 63) and asks us to bear witness to the ways such violence contributes to the “total collapse of structured memory” (p. 67).

The essay titled “Blueberries” falls midway between the city and the museum and begins with the repeating phrase “I was in America at a very expensive…”. Savage recalls and reflects upon eating the “preferred snack of voracious girls and women” (Beeston, 2020) in various expensive American locations dressed up in mediocrity, materialism, money and maybe masculinity too (Savage, 2021, p. 42). “Relishing the colour of it inky and regal” while “pushing velvet blueberry skin against the roof” of her mouth, Savage expresses her compulsion, confusion, and collusion with the morality of this culture she readily consumes and now contains within her. She agonises over whether or not her participation in it makes her a bad person but seems to sigh and comfort herself by stating that she is not really a bad person, but more a person “trapped inside a matrix of bad ideas bad histories bad reactions” (p. 49). And suddenly, I am no longer with her. By her own admission, Savage (p. 82) cannot bear to look at humanity and all of the enshrined and systematic trouble it has caused, and so she thinks that maybe she’ll just walk away and leave it as it is. Did Savage really just spit out the response-abilities her young-white-race-class-able-bodied positionality hold now that she has tasted them because they have turned this fruit bad? Because her knowing of these known things is now too sour for her to stomach and no longer to her taste? Confessing, claiming, and choosing, do not make the response-abilities go away Ellen Savage, they bury you more deeply and difficultly in the comfort and complicity of colonial truths.

Want an orange?

I have a difficult relationship with citrus; I have always never loved citrus. I hated taking oranges to school for lunch. They were messy and difficult to eat; and I did not like the sticky and pungent scent that seemed to linger for days after on my hands. I learnt to tolerate mandarins; but only because Mum made sure she peeled them for me and wrapped them carefully in glad wrap; Mum was always gentle like that. There are only two specific moments now where my taste buds relent and agree that orange consumption can be accommodated—immediately after a marathon, or while out bush, in both instances the risk of dehydration is very real and very present. Jeanette Winterson has an equally difficult relationship with citrus, specifically oranges, but her mother is not gentle. The title of her coming-of-age semi-autobiographical novel Oranges are not the only fruit (1985) tells the story of a lesbian girl growing up adopted in an evangelical family and English Pentecostal community.

For Jeanette, oranges are a cure-all for confusion to be eaten in moments of contemplation trying to find out why “the world is very quiet” (p. 24), a source of comfort handed to her mother upon realising that the world does not run on “simple lines” (p. 26) after all, and a harsh awakening to the reality that even the most well-constructed orange peel igloo falls down and fails because no matter how hard you work at it to make it work, putting an Eskimo inside is practically and politically naïve (p. 27). For Jeanette, the consumption of oranges is a sign of commitment and conformity to the rules and regulations laid down by powerful social and cultural institutions—the Church, marriage, and heterosexuality. “You’ve got to”, Jeanette’s mother insists, “Here, have an orange” (p. 38). Melanie, a childhood friend with whom Jeanette shares her first sexual relationship, asks “Want an orange?” (p. 119) in a chance meeting years later at a Christmas carol concert and begins to peel it. Jeanette grabs her arm and makes her stop—when the two girls “unnatural passion” was discovered by the congregation, Melanie caves and repents immediately. For Jeanette, her refusal to atone leads to public shaming, punishment and a 36-hour exorcism in her mother’s parlour. Without food, water, or light, and feeling more than a little lightheaded, she encounters her demon. It appears at her elbow in bright orange and promises to help keep her in one piece by showing her how to hold on to her difference differently. She decides that no matter who much she may have loved Melanie there and then, here and now she cannot accept the stock standard fruit of status femininity her friend has surrendered to and now offers. It all ends in tears of rage for Jeanette’s mother. “Have an orange” (p. 129), Jeanette suggests and gestures towards a line of citrus perched on the windowsill as salve for her daughter’s wicked perversity. I don’t have the same relationship with oranges that Jeanette has. I have never thought of them as pretty, a helpful friend, an icon, or as a sign of giving up and giving in. But I do understand being in relationality with fruit—the felt sense of belonging while at the same time bordering on the edges of the binaries that the taste, texture, and tang a piece of fruit might harbour in.

Really, for me?

The more I think-with fruit—and why not? “Think we must: we must think”, Haraway (2016, p. 40) urges, if we are to change the story of capitalist and colonialist compelled consumerism that Ellena Savage conveys in Blueberries—the more I think about moments where fruit are companions becoming-with us on this stage we call life and death, replete as it is with love, hatred, and everything in between. My wondering and writing here about thinking-with, becoming-with, being in relationality-with fruit was altered irrevocably after reading Robin Wall Kimmerer’s (2013) Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge, and the teaching of plants, and more specifically, the chapter titled “The gift of strawberries”. This is one of the most moving pieces of writing I have ever read. In this chapter, she speaks of being “raised” by strawberries, wild and sweet gifts wrapped in red and green scattered at her feet (p. 39), whom she prefers to call “heart berries” or ode min in her Native language of Potawami. For Potawami peoples, strawberries originate from Skywoman’s daughter’s heart who died giving birth to twins. Heartbroken, Skywoman buried her daughter in the earth and “her final gifts, the most revered plants, grew from her body. The strawberry arose from her heart” (p. 39). Being in-relationality-with strawberries as heart berries positions them as family for Kimmerer, in an intimate and infinite gift economy of reciprocity between people and fruit. She writes of wild strawberries as sovereign and sentient, giving and taking in-relationality-with humans, and both carrying “bundle of responsibilities” (p. 44) attached to living and loving together in a world where generosity and gratitude take the place of greed. “Really?” Kimmerer pauses, kneeling before a patch of wild berries dimpled and snuggled under dewy leaves, “For me?”

Apples, that place where love resides

My thinking-with Kimmerer’s heart berries begins to wonder towards love. You can see love working everywhere once you start looking. I reach for an apple from the 10kg box recently purchased from a roadside stall in Applethorpe, Queensland currently occupying the third shelf in my fridge. I have always thought of strawberries, not tomatoes, as love apples; either way, I love apples and particularly the Granny Smith green variety. The round fruit is smooth and cold in my hand; and drawing it to my lips its freshly picked scent fills my mouth with memories of my Nana Barlow.

There I am with her at the small, red laminated table in her warm kitchen. She is holding a paring knife in her stiff and swollen fingers, expertly peeling and slicing apples for a home-made pie. I can only ever remember Nana’s hands like this, cruelly gnarled by rheumatoid arthritis. Mum always said that the disease had kicked in after Nana had in turn kicked a football with bare feet as a little girl—the impact of the hard leather had damaged her bones you see, and under no circumstances were my sisters and I allowed to do the same. You can see in photos of Nana as a young woman that the condition had already invaded and taken her body captive, and while I know now that rheumatoid arthritis is an auto-immune response, I can count the number of times I have kicked a football on one hand. I can only imagine the pain Nana was in as she prepared that those apples; her strong gentle spirit must have pushed it aside because all I saw and felt was her love. A sweet pastry case she prepared earlier is blind-cooking in the oven, alongside roast lamb and potatoes basted in dripping. Carefully, she layers the thin tart slices of apple with sprinkles of brown sugar, cinnamon, and lemon juice. I watch as she expertly crimps the crust with her thumb and index finger, making small cuts at 1.5cm intervals around the edges of the pastry, then folding over at a 45° angle and pushing down to seal. There is now a pretty halo of leaves encasing the fruit and Nana places small lattice crosses across the top to complete the picture.

Taking a half-a-dozen apples or so from the recently acquired box in the fridge I begin to peel and slice them—I promised the boys I would make them an apple pie, just like the one my Nana made. Sometimes I add blueberries or strawberries, but not today. In this moment I immerse myself in remembering my Nana’s love, the gift of her heart she shared in an apple pie. I think about the way the touch, scent and taste of Granny Smith apples always takes me to her, close, so close; a punnet of blueberries to summer, my sister, and Auntie Florence; and the shape of strawberries to our hearts interwoven across time and place. I have learnt so much about our response-abilities and sense-abilities to love from thinking-with, becoming-with and being in relationality-with people and fruit—or as Donna Haraway (2016, p. 2) might say, by making “oddkin” between us. Lessons about the immediacy and impermanence of life; lessons that speak to individual and collective comfort, conformity, and complicity; and, lessons that bring fragility, family, failure, and freedom into the same frame. I have enough pastry left to add a final flourish to the centre of my apple pie, that place where love resides—lessons gifted full circle so that Max and Hamish too, may learn these things and more by heart.

References

Buchanan Smith, D. (1973). A taste of blackberries. Scholastic Press.

Dickinson, E. (2016). Emily Dickinson’s poems: As she preserved them (C. Miller, Ed.). The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Plath, S. (2000). The unabridged journals of Sylvia Plath. Anchor Books.

Savage, E. (2021). Blueberries: What kind of body makes a memoir? Text Publishing.

Wall Kimmerer, R. (2013). Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom scientific knowledge, and the teachings of plants. Milkweed Editions.

Winterson, J. (1985). Oranges are not the only fruit. Vintage Press.

Berry image Photo by Susanne Jutzeler, suju-foto : https://www.pexels.com/photo/strawberries-and-blueberries-on-glass-bowl-1228530/Berries

Aaah Liz love, you’ve done it again! Brought a tear to my eye, a warm glow to my heart… many thanks for another beautiful piece of writing. i thought i was all caught up on your blog so was delighted to realise i hadn’t read this one through yet! My nana used to do a rhubarb and apple pie and i loved helping with the lattice/woven top. YOUR pie is magnificent! A pie that will stay in your boys’ memories forever xxx

Thanks Nicola 🍎apples and rhubarb are a match made in heaven – complimenting each other beautifully. I’m glad it’s returned some mouth watering memories to you!