“She was a homely body; an old lady in a plaid shawl which was fastened by a large cameo; and she sat in a basket-chair, encouraging a spaniel to look at the camera, with the amused, yet strained expression of one who is sure that the dog will move directly the bulb is pressed” — Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own [1]Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own, Hogarth’s Press, 1935, p. 32.

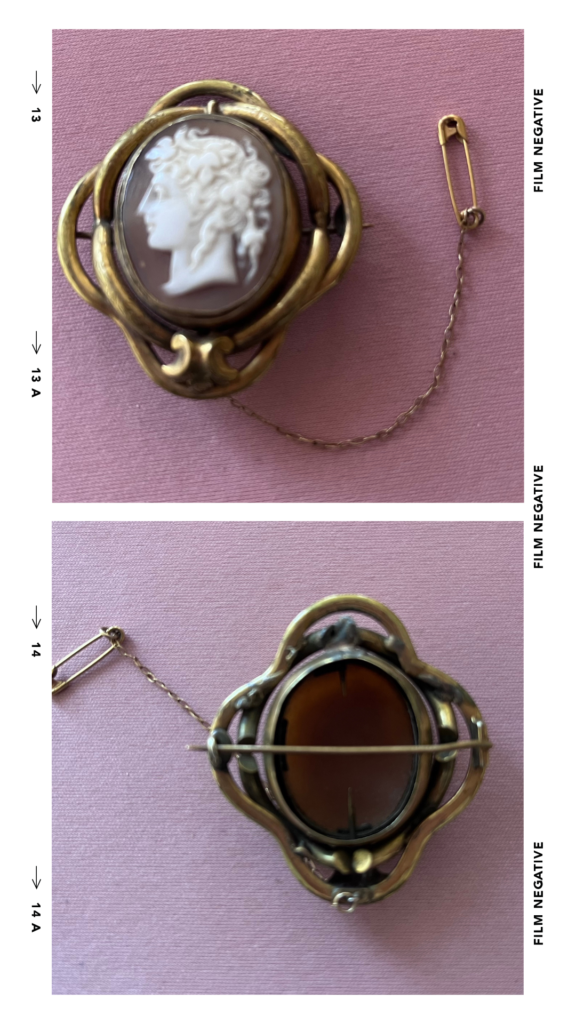

Antique cameo brooch

cameo brooch, shell, 9ct gold, c. 1850-1870

57mm x 62mm x 11mm

Cape Town, South Africa

In the 19th century, cameos gained popularity due to affordability and easy travel to Italy. Middle-class Britons on the “Grand Tour” cherished cameos as souvenirs, symbolizing status and sentiment. Worn as pendants or brooches, they showcased refined taste and sentimentality. Described by an anonymous writer in 1871[2] Anonymous, cited in Lauren Miskin, “The Victorian ‘Cameo Craze'”, Victorian Review, Vol. 42, No. 1, pp. 167-184. as an “ornament more exquisite to a lover of art than glittering jewels”, Queen Victoria’s fondness for cameos made them a feminine everyday jewelry choice, reflecting her monarch image. This uncommon left-facing shell cameo, featuring Victorian-style relief with a straight nose and ornate hair and a c-clasp with hand-made tube hinge, exemplifies this era’s artistry. A bridge between art, culture, and fashion, 19th-century cameos encapsulate historical depth within delicate craftsmanship.

Gifted by Florence Flood to her niece Elizabeth Mackinlay in memory of her grandmother Daphne Abigail Mackinlay.

11th August 1910

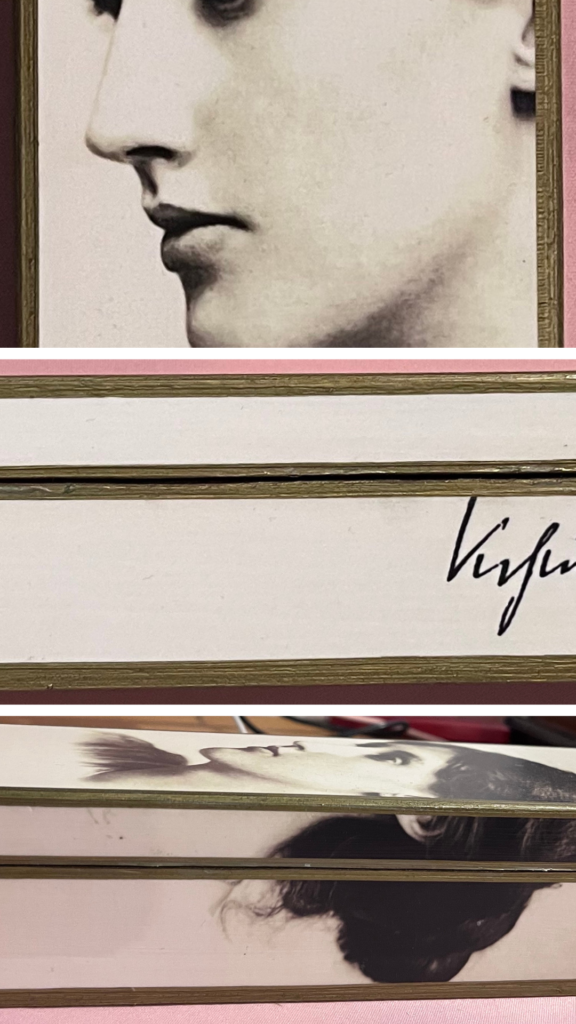

Margaret Alexander with her daughter Daphne Alexander and son Jack Hall

Daphne held her brother’s hand tight as they stood by the side of the four-poster bed in the grand house at Clifton on Lea. The walls of the dark paneled room were swollen with sickness and sadness, and she was finding it difficult to breathe.

“Jack,” she whispered not wanting the other people around them to hear. Daphne didn’t really know who they were, only that they were her wealthy father’s family and that they did not approve of her mother on account of her being an actress. Oh, how her mother loved to sing and dance! By day she was Margaret Alexander but at night on the vaudeville stage she transformed into the elegant and exquisitely talented Tottie Hall.

She tugged on her brother’s sleeve. “Jack, she’s only sleeping, isn’t she?”

She could not take her eyes away from the copper coins they had placed on her mother’s eyes. Daphne had seen metal discs like this before, glinting in the flames of candles, when she had accompanied her uncles to the homes of Jewish friends in mourning. But her mother’s pennies were dull, and she felt all the warmth and light she had ever felt in the world beginning to drain away.

Her brother held his face in his hands and his shoulders shook.

“Jack,” she said softly, “When is she going to wake up?”

Lying wide awake in a strange bed in her Uncle Joe’s house in the affluent suburb of Clifton in Cape Town, Daphne shivered. She was only five years old, and both of her parents were gone. Her father Benjamin Alexander had died when she was a toddler. She couldn’t really remember him, but she liked to think it was his voice that softly greeted her in the dreamy space between night and day in the manner reserved especially for her—“My Queenie, the one and only”, he would say.

Daphne squeezed her eyes shut and a lump rose in her throat. She was not sure how much longer she could stomach the smell of oranges and castor oil that she was being forced to digest daily by her South African relatives. She had overheard Uncle Joe and Aunt Hilda say they only wanted her to become a permanent part of their family, not Jack. It was true that her half-brother was head strong, but in her eyes, he lived and loved her fiercely; and besides, he was the only person she had left. She could not and would not lose him too.

She was certain that one day there would be a knock on the door and her beautiful mother would be standing there to take her into her arms and to take her home. Her fingers lightly brushed the fine carved relief on the cameo brooch she held in her hands. It had belonged to her mother and Aunt Hilda had given it to her the day her mother had died, not wasting a moment to sort through her possessions. Daphne pressed the cameo brooch to her chest. It brought her comfort knowing that her mother had once held this object in her hands too, that perhaps she had been gifted the delicate piece of jewelry from her grandmother, and her grandmother from her mother before that.

123 years later, 11th August 2023

My Nana’s cameo brooch caught my attention recently when asked to bring a personal and professional artifact to a university leadership retreat. Thinking back through my mother’s—as I often do—I selected a wooden pencil case with a portrait of Virginia Woolf and the inherited jewelry piece, and the portrait on both seemed to link them inextricably together. When my grandmother Daphne Abigail Mackinlay passed away, the most treasured of her possessions gifted to me were the letters we had written to one another and two silver tablespoons. The pages of correspondence, now carefully tied together with pale blue ribbon, sit in an old suitcase that was used to keep our toys at Nana’s house and I turn to these in moments when life twirls and twists in ways that seem to bring thoughts of her close. The cutlery, slightly worn on the left side on account of Nana being right-handed, sits in the kitchen drawer and I use them every day. The paper and metal left to me by my grandmother might look ordinary, but all I need to do is hold them to remind me where my heart is.

When I last saw Auntie Florence, Nana’s only daughter, she handed me a small square gold and black cardboard gift box. Preparing to celebrate her 90th birthday and while still as spritely as ever, she had decided it was time to begin passing along family items.

“Beth, I was sorting through a container of this and that of things that belonged to Nana”, Auntie Florence paused, “and I remembered that you were the only granddaughter who doesn’t have a piece of her jewelry”.

“Oh, but I have something more precious than that”, I smiled, “I have her silver tablespoons!”

Auntie Florence laughed softly and shook her head.

“No, I would like you to have this—it’s Nana’s cameo”.

The enchantment of objects

My grandmother’s cameo might be just an object made from shell carved in relief and framed in gold. Yet the longing that overwhelms me when I hold this vintage piece of art-jewelry in my hand, tells me that its materiality and its affective power are so much more than that, and one and the same. Her cameo holds a story at once personal and political that has travelled through time and across nations. It holds the dreams of a dancing girl and the grief of her daughter. It tells of a world in colonial expansion and of light-hearted theatrical performances for the masses. It provides a glimpse into notions of fashionable commodities of femininity and the cruelty of family in times of crisis. It embodies a maternal lineage that moves backwards and forwards between generations of resilient women that can never be broken and will always return. Piecing together traces of Nana’s cameo story has sent me thinking and wondering about the enchantment of objects, for I am indeed enthralled by this one. In her 2016 work The enchantment of modern life, Jane Bennett[3]Jane Bennett, 2016, The Enchantment of Modern Life: Attachments, Crossings, and Ethics, Princeton University Press describes “enchantment” as a particular kind of mood which begins with a meeting that you were not quite expecting. After the initial encounter the feeling quickly evolves into a sense of being at once spellbound and snapped into a condition where everything is extraordinary—now captured, the enchantment carries you away. It’s true, my grandmother’s cameo has a strange and alluring vitality, a certain kind of “shimmer” drawing me to the idea that this object is a central player in the story of who my grandmother was and who I am. While for my grandmother, the conditions of the cameo’s arrival were unhappy, its entrance into my life is replete with happiness. It is a “happy object” as Sara Ahmed might say[4]Sara Ahmed, “Happy objects”, in The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Gregor Seigworth and Melissa Gregg, Duke University Press, 2010, p. 29-51. because it puts me into intimate contact with the happenings of her life—the good and bad things that happened to her which remind me that strength is often born of struggle, chance more so than choice is part of the play, and that loss is a lesson in learning how to love. The curio

us ability of this cameo is its capacity to resonate in-between us, to sing—or perhaps even to (en)chant)—side by side on the piano stool as my grandmother and I laugh at our clumsy attempt to play our very own “two-hands” version of “The Can Can”.

A heart shaped locket on a long silver necklace paired with a small silver heart stud in my left ear are the items of jewelry I wear every day, and without them I feel undressed and unsettled. I have never been a brooch wearer but my research into the history of the “cameo craze” suggests that converting my grandmother’s jewelry into a pendant would be in keeping with Victorian fashion. The cameo is light as it hangs around my neck on a delicate silver 65cm chain, resting gently beneath my breastbone. It could be referred to as a “statement” item, a piece of jewelry that encompasses the wearer’s uniqueness and character, while simultaneously eliciting and conveying powerful emotions. I would like to think that it is at once many things —a declaration of maternal ancestry, an acknowledgement of the life my grandmother led and her achievements, and an affirmation of whatever the world might think of us as women, no woman is to stand alone. Thinking back through our mothers we can and will be strong-minded, strong-hearted, strong-souled, and strong-bodied for strength and beauty must go together.[5] Louisa May Alcott, 1869, An Old Fashioned Girl. Roberts Bros. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/2787

References

| ↑1 | Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own, Hogarth’s Press, 1935, p. 32. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Anonymous, cited in Lauren Miskin, “The Victorian ‘Cameo Craze'”, Victorian Review, Vol. 42, No. 1, pp. 167-184. |

| ↑3 | Jane Bennett, 2016, The Enchantment of Modern Life: Attachments, Crossings, and Ethics, Princeton University Press |

| ↑4 | Sara Ahmed, “Happy objects”, in The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Gregor Seigworth and Melissa Gregg, Duke University Press, 2010, p. 29-51. |

| ↑5 | Louisa May Alcott, 1869, An Old Fashioned Girl. Roberts Bros. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/2787 |

Beautiful Beth – a lovely resting place for a very treasured cameo and so many memories of a beloved “Nana’ – Auntie Florence.

Thank you Auntie Florence – the best gift I could give in return to you was to write a little of Nana’s story. Much love always, Beth x

Beth, such wonderful heartfelt words. So glad that mum passed this onto you and as only you will do treasure it whole heartedly. You truly have a gift. Love to you and your boys. Continue to be the strong and beautiful person that you are

Love Kaylin xx

Hi Kaylin, so lovely to hear from you and I’m so glad you liked this piece of writing. I loved writing it and I hope it shares a little of Nana’s story – our story – with those who loved her! I think of you and your growing family often and send you much love on the wind. Beth x

A beautiful story Liz, thank you for sharing this ,

Sue xx

Thank you for reading and your lovely words in reply Sue – I loved writing this piece and am truly enchanted by the stories this object has evoked. Liz x

so evocative and moving (as usual!) … thank you Liz. xxx