As a matter of fact, miraculous and magical things happen

I can’t remember the first Alice Hoffman book I read. I don’t think it was Practical Magic (1995), even though I loved the movie of the same name starring Nicole Kidman and Sandra Bullock. Practical Magic tells the story of twin witch sisters Sally and Gillian who find themselves in Massachusetts to be raised by their aunts Frances and Jet after their parents’ death. Their new home is indeed an unusual household where they are taught the uses of “practical magic” and soon learn that being a member of the Owens family carries a curse—those they fall in love with are doomed to an untimely death. Together, Sally and Gillian use their powers to struggle against the family curse and a swarm of supernatural forces that threaten the Owens’ lives. Daily life turns to fairy tale in this magical realist story where spilled salt is thrown over shoulders, black soap turns women’s skin luminous, deathwatch beetles click and clack, and nine times tables are recited backwards to cause all manner of physical harm. A violent man is turned from trouble into a toad as the Owen’s women individual and collective heartbreak puts them on a path to true love.

Practical Magic overflows with the everyday power of women’s wisdom, kindness, and love and it is this aspect of Alice Hoffman’s writing that draws me to her—her stories matter because they are most simply and movingly about women practicing the art of real life in a world which is “uncertain and wondrous and generally resistant to our attempts to control it” (O’Hara, 2003, p. 198).

Spinning gold out of straw with words

Born in New York City on 16th March, 1952, Alice Hoffman graduated from Adelpi University with a BA majoring in anthropology and literature before receiving a Mirrellees Fellowship to the Stanford University Creative Writing Center and an MA in creative writing, and has published over thirty novels, three books of short fiction, and eight books for children and young adults. Hoffman describes herself as a working-class girl who loved to read, who loved fairy tales, and who loved nothing more than to sit at the feet of her Russian grandmother and listen to her stories (Lawrence, 2007, p. 4), where as a matter of fact, miraculous and magical things could and did happen (Goddu, 2015). She embraces the label “magic realism” often applied to her work, “Magic in fiction is a long tradition” she explains “One of the reasons we like fables and fairy tales is that they’re emotionally true and page-turners at the same time” (O’Hara, 2003, p. 198)—“they get to the heart and soul of the matter in a subtle way, disguised the way the truth is disguised in a dream” (Michalski, 2013).

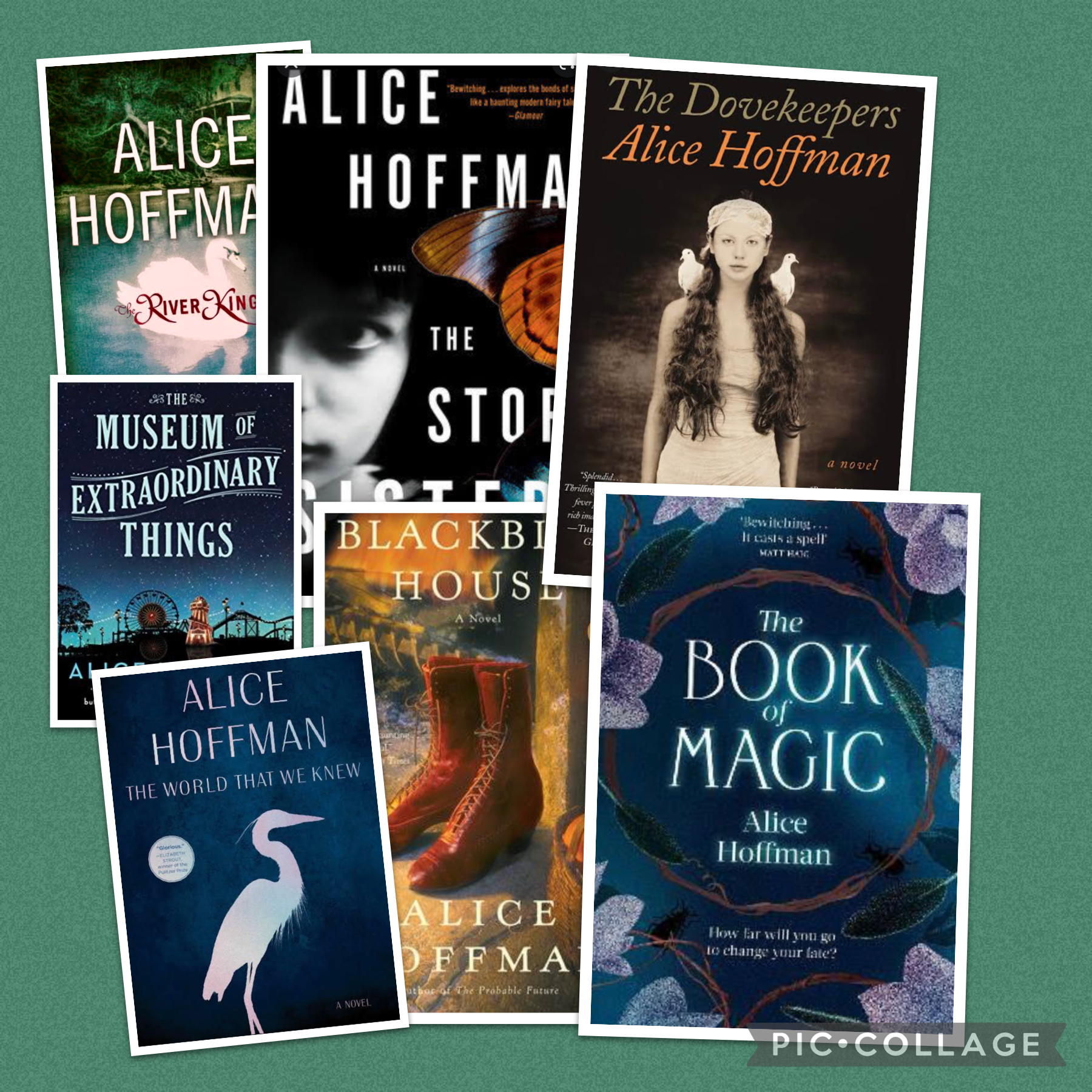

Each time I walk past her books on my shelf I am touched by the lives, loss and loves the stories hold. Of Coralie who appears as a mermaid in her father’s boardwalk show and swims her way to a better future in the The Museum of Extraordinary Things. Of Yael, Revka, Aziza and Shirah, the four insightful, intense and independent women who survive a siege in ancient Masada through the strength of secrets kept and shared in The Dovekeepers. Of Hanni, Ava, Lea and Ettie who sacrifice everything and draw upon remarkable courage to resist and survive the violence and horror of the Nazi regime in The World that We Knew. Property Of, The Story Sisters, The River King, Blackbird House, the remaining three in the Owen’s family quartet Magic Lessons, The Rules of Magic and The Book of Magic and so many others—like Rapunzel, Alice Hoffman “takes whatever is bad” in the world and women’s lives, and spins and spins her words until she has created “gold out of straw” (Lawrence, 2007, p. 4). All artists, she says, have a similar thing in mind—“to make something beautiful out of dust and ashes” (Book Reporter, 2017).[2]

The words Alice Hoffman uses to talk about her writing draw me closer still. She believes that reading and writing gives permission to both reader and writer to “imagine, to create a world, to make history come alive, to take [a] secret and add your own” (Hoffman, 2011, p. 8). She believes that if you can imagine it, you can tell it for it is “within the realm of the imagination that we find our truest stories, stories of the heart and soul” (Hoffman, 2011, p. 7). She believes that the deepest truths are found in and best served by fiction (Hoffman, 2011, p. 7). She believes that stories hold “love and loss and the ability of the human spirit to survive great sorrow” (Lynn). She believes that a writer charts an “emotional landscape” (Hoffman, 2011, p. 7), and that “once the world feels ‘real’ in an emotional sense, anything can happen” (Lynn). She believes that every “writer’s voice is a fingerprint” (Book Reporter, 2017), that every person carries their own story, and that each and every one of us is a book, a “volume yet to be written”. She believes that stories “define who we are, who we wish to be. They warn, the remind, they cut so deeply they can leave a scar. If left untold they can linger and grow heavier, for every tale is made for two: The teller and the listener” (Hoffman, 2011, p. 6).

Because, Blue Diary

“If a woman is in trouble, she should always wear blue for protection. Blue shoes or a blue dress” (Practical Magic, 1995, p. 101).

Everything she believes about reading and writing moves me closer and closer to the truths I hold about the capacity of stories to tie themselves to life, even if ever so delicately by a single thread at the corner. My imagination wants me to believe that Alice Hoffman and I have always been a reading and writing couple—her words seem to have been a part of my literary world forever—and while I cannot I remember exactly which work of hers I read first, the last book of hers I read, Blue Diary has etched itself indelibly everywhere. It was the only Alice Hoffman book on the shelves of Archives Fine Books in Brisbane on the day I was there and the complementary colours on the spine catch my eye as does the five letter second word in the title. Gently removing the book, I turn the cover over to find a flock of blackbirds flying across a purple-tinged cobalt sky above a golden cornfield in sunshine and in shadow. “It’s the last Monday of the month”, Hoffman’s begins, and I snuggle into the familiar rhythm of seasons which characterise the setting of her stories. The blurb on the back gives nothing away aside from the fact that Ethan and Jorie are the perfect couple—handsome, attractive, dreamy, and popular, and madly in love after thirteen years. The first fifteen pages positively radiates their individual and collective perfection, luring me into their perfect world where they make perfect love with their perfect bodies on a perfect June morning, in the afterglow fixing the sweetest iced coffee and strawberries picked from their perfect garden, before embarking on a perfect day at work in jobs to which they are perfectly suited and perfect. Then 12-year-old Kat Williams makes a phone call that will change their life irrevocably and I am completely unprepared when it happens. Dorothy Allison says that when she sits down to make her stories, she wants to “take the reader by the throat, break her heart and heal it again” (Allison, 1994, p. 181) and I can’t help by wonder if Alice Hoffman and her are literary friends. On page 31 I stop breathing. Jorie’s perfect morning is interrupted by a knock at the door whereupon Ethan is taken away in handcuffs and detained in a cell in the local county jail for the murder of 15-year-old Rachel Morris 15 years earlier. Jorie falls to the ground and does not stand again until page 289. On 4 November 2016, the police came knocking at my door and arrested my then husband too. Six years on he sits in jail waiting to be sentenced and even though I am breathing, I haven’t managed to stand—yet.

There is so much about what happens next in Jorie’s life which mirrors my own. How the first time and the last time you visited him in jail you cannot believe the man you lay next to for 20 years is staring back at you wearing the khaki clothing that marks him horrific. How you cannot believe that you married a man capable of such horror and of which, for all that time, to your horror, you were completely unaware. How there are times when the truth of what he has done hurts horribly and you choose to avoid prying glances, snide remarks and accusing looks by locking yourself inside. How your heart cannot bear the horror and your body does its best to simply waste it all away. How you want to show compassion and forgive him but are torn because you know you will never the forget the horror of what he has done and surely those he has hurt deserve your compassion more. How you keep hoping at soon you will wake up from the horror you now carry around inside you as though it “were part of your blood and bones” because you know that “when that happens, there’s nothing you can do to forget” (Hoffman, 2002, p. 30).

Jorie begins to find a way through the horror when she finds Rachel Morris’ blue diary—a pale blue leatherette trimmed in gold (Hoffman, 2002, p. 205). She carries it with her everywhere—to the store, to work, to the bank, to bed, to the jail—holding it close to her when is alone (p. 258), a reminder that some things are never over “they stay with you until they’re a part of you, like it or not” (p. 237). Rachel’s blue diary is locked and she finds the key on a metal rack amongst Ethan’s personal belongings left behind in the garage. There is one key which has no tag, attached to a strip of frayed blue ribbon. Corroding and cheaply made, Jorie knows it’s the right one; it has been in their home for thirteen years, but it still turns the lock (p. 285). She sits in her now imperfect garden and begins to read.

Returning to the ending to begin

Halfway through reading River King, my partner recently asked me what it is about Alice Hoffman’s writing that has me so spellbound. The answer was simple, “Because, Blue Diary”. Blue Diary, like so many of her stories, plunges without fear or hesitation into the life of a woman “practicing the art of real life” (O’Hara, 2033, p. 197) when the reality of that life is, without warning, brutally torn apart. Blue Diary is a story about secrets and suffering, the capacity of the soul to survive, to make sense where none can be found except in the scars left behind, in an ongoing search for some semblance of peace. Such things, as they happen in Blue Diary, are fictional marks on a page but they speak of a world—indeed, a world so close to my world—which is all too real, and most times unspeakable. Jorie did not murder Rachel Morris, but the truth is that her husband did, and no matter how many times people say it wasn’t you it was him, his truths will always be part of her own. At the end of Blue Diary, Jorie moves on by imagining everything that is out in front of her, something that is only possible after returning to the ending where it all began. My ending begins not in a blue diary, but a purple one. Perhaps if I hold onto Alice Hoffman’s belief that it is possible to take whatever is bad and just keep spinning and spinning until it becomes a story beyond loss and sorrow, one day I will have the courage to return to the marks on the pages of my purple diary and turn them into words which speak the truths of my world.

References

Allison, Dorothy. (1994). Skin: Talking about sex, class and literature. Firebrand Books.

Book Reporter. (2017). “Author Talk”, 12 October, https://www.bookreporter.com/authors/alice-hoffman/news/talk-101217

Goddu, Krystyna Poray. (2015). “Q&A with Alice Hoffman”, Publisher’s Weekly, 3 March, https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/childrens/childrens-authors/article/65755-q-a-with-alice-hoffman.html

Hoffman, Alice. (1995). Practical Magic. Penguin.

Hoffman, Alice. (2001). Blue Diary. Berkley.

Hoffman, Alice. (2011). “Introduction: Storyteller”, Ploughshares, 37(4), pp. 6-8. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/460305/pdf

Lawrence, Vanessa. (2007). “Dream weaver”, WWD: Women’ Wear Daily, 193(6).

Lynn, David. “A conversation with Alice Hoffman”, https://www.kenyonreview.org/site/wp-content/uploads/Hoffman-Lynn.pdf

Michalski, Liz. (2013). “A Q&A with Alice Hoffman”, 29 March, https://writerunboxed.com/2013/03/29/interview-with-alice-hoffman/

O’Hara, Maryanne. (2003). “About Alice Hoffman”, Ploughshares, 29(2/3.

Oh darling … sob. Truly, this piece has broken me, broken my heart. i am properly crying, and loving you for it, realising how long it’s been since i properly cried, and how good it feels. i had intimations from your book, but no idea really … and still no idea really but intimations are enough. May you weave the wyrd of your becoming with shimmering threads, wondrous and divine. x

What Nicola said… feeling with you Liz…

Thank you Dawne, it means the world to have you with me x

Thank you Nicola – your response means more than those two words can say – these truths are hard but maybe our tears will make them able to be held ❤️🩹